[IAHR Talks] Interview with Roger Falconer. Focus on water security

#IAHRTalks

“COVID-19 has created many challenges in terms of water security and, most notably, what are the effects of the disease in entering the water system and how does the disease advect and diffuse through the system? However, it has also brought many opportunities in terms of global water security”.

“COVID-19 has created many challenges in terms of water security and, most notably, what are the effects of the disease in entering the water system and how does the disease advect and diffuse through the system? However, it has also brought many opportunities in terms of global water security”.

Roger Falconer, Past President of IAHR (2011-15), chair of the IAHR working group on Global Water Security and Emeritus Professor of Water Engineering at Cardiff University, School of Engineering, shares with us his views on water security and on the role the association plays in this regard.

David Ferras, vice-chair of the IAHR technical committee on education and professional development, interviews Roger Falconer.

Can you recall when and how you became interested in water science?

I first became interested in water science and engineering at the age of about 6. I was born in a small town in west Wales, in the UK, and my neighbour was an eminent civil engineer, working on Swansea Docks. They had no children at that time and would often take me with them to the Elan Valley dams in mid-Wales. These dams are magnificent old structures and excited me into wanting to become a civil engineer, specialising in water and designing dams.

Which of your career achievements do you feel most proud of?

I have been fortunate in my career in receiving a number of career achievements which have meant a lot to me personally including, for example, being elected a Fellow of the UK Royal Academy of Engineering, a Foreign Member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and President of IAHR (2011-15). However, one of the most rewarding career achievements has been recipient of the Cardiff University School of Engineering Large Class Teacher Award, which I received on several occasions. This award is made by the students (typically 150 annually) and it has always been an honour to me to receive this award from the students and for teaching them Environmental Fluid Mechanics.

You’ve spent much of your career in academia but have also worked closely with industry. From your perspective, what should be the right workload balance of a junior professional following an academic career in terms of research, education, and industry?

You’ve spent much of your career in academia but have also worked closely with industry. From your perspective, what should be the right workload balance of a junior professional following an academic career in terms of research, education, and industry?

I have always benefitted enormously and enjoyed the privilege of working closely with industry. Whilst at Cardiff University (1997-2018 as an employee), my post was continuously sponsored by consulting companies and I had a particularly close working relationship with these companies, and sometimes with their clients too. Not only did I find it beneficial to experience the way in which companies operate, but I also found that engaging through research on industrially related projects enabled me to bring that experience to students, making lectures more interesting and informative for the students, and thereby increasing my personal level of job satisfaction. I would advise any early career researchers in research and education today to work as closely as possible with companies. In my experience a successful partnership with practitioners helps focus your research, improves the impact of your research and also makes your lectures more interesting. Furthermore, strong links with industry enable you to change your career path more readily if you wish to do so in the future.

Picture: The Beautiful Craig Coch Dam, Elan Valley, Wales, UK (1897).

How has the “IAHR member profile” evolved since you first got involved in the association?

The IAHR member profile has changed enormously since I first joined IAHR in the early 1980s. At that time IAHR was dominated by members from the US, Europe and Japan and presentations at congresses were almost totally focused on hydraulics and hydrodynamic modelling (experimental and computational). However, over the years the scope of the association and the interest of the membership has broadened enormously to include understanding the hydrodynamic and sediment transport processes as vectors for a wide range of water quality constituents etc. The membership has diversified too, to include many more members from the Asia Pacific region and, in particular, to include many more women in the association. I was particularly pleased to note that 50% of the elected members to the last Council were women; not many organisations can claim to achieve such a transformation so rapidly. Having said that, we still have much to do as our association still has not had a woman President since its formation 85 years ago.

Including the word hydro-environment in the IAHR acronym has allowed for a broadening of topics, to such an extent that the new technical committees have become very active and key for the development of the association. In your opinion, are the classic technical committees (e.g. fluid mechanics, fluvial hydraulics, hydraulic structures, etc.) still the pillars of the association?

In my view IAHR technical committees need to be reviewed regularly. Whilst IAHR must always have committees embracing Fluid Mechanics etc., I also believe that we have to become more practitioner focused and consider how our technical committees can more closely replicate the interest of practitioner and specialist hydro-environmental organisations, such as HR Wallingford, Deltares and Dhi – to mention but a few. I would therefore argue that we should be mindful of the divisions/sections within such organisations and how well is IAHR reflecting these company divisions. Ultimately no private company maintains divisions in fields which are no longer of interest to their clients, i.e. usually governments and non-profit funding organisations. If IAHR is to grow in the future, then I believe we must be mindful of the end user needs of our research and engineering, as is now the case for research funding agencies in most countries.

IAHR academics deal with modern hydro-environmental problems; also industry deal with them, especially when these have high societal impact; young professionals feel attracted to industry when starting their first career steps; and a good quarry of young professionals is crucial for IAHR. Could you develop a bit on the drivers that move such spiral? What key elements should we strengthen in order to have a more robust growth of our young professional networks?

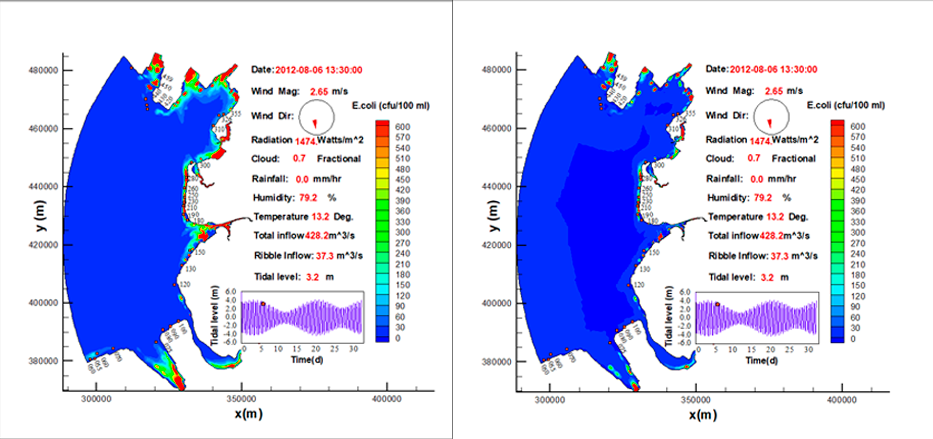

In my view the important points that all of us within the IAHR community should be mindful of are two-fold: (i) industry, or practitioners (e.g. including government agencies etc.), are often not directly interested in the hydrodynamic or sediment transport processes. For example, in terms of bathing water compliance and the design of a long-sea outfall, industry and regulatory organisation managers are concerned with faecal indicator organism (FIO) and/or gastroenteritis disease burden levels, but not so much the velocity field; and (ii) the hydrodynamic and sediment transport processes are the governing vectors that move the FIOs from the catchment (including diffuse source inputs from the land or combined sewer overflows) to the bathing reaches and we need to ensure that IAHR continuously promotes the importance of getting the hydrodynamic and morphological processes predicted as accurately as possible. If the hydro-morphological processes are not accurately predicted, then the optimal design will not have been produced and the scheme will be over or under designed, leading to substantial losses (usually in millions and possibly billions of dollars). Hence, the IAHR community has a responsibility to ensure that industry and government agencies etc. are always using the most accurate hydrodynamic and sediment transport process predictive tools (including data collection and analysis, as well as modelling) in designing new schemes for a wide range of projects. These projects can range from flood alleviation schemes to turbine design, to water quality, to eco-system services etc. I believe this message is particularly important for young professionals, who may often be encouraged to impress the practitioner by focusing on the end-users interests, rather than ensuring they also highlight the importance of first getting the water science and engineering right. We are often our own worst enemy in terms of promoting the importance of accurately predicting complex hydro-environmental processes.

Since the COVID-19 health crisis many events have been forced to take place online. Hybrid (face-to-face and online) conferences seem to be the model to follow even after the crisis. What key elements of a World Congress do you believe could (or should) be offered in a hybrid format?

The COVID-19 health crises has been terrible for so many citizens worldwide and it is perhaps premature to discuss the lessons learnt from this crises. However, IAHR is a global organisation with members across the world and all working at different time zones. One thing that COVID-19 has taught us is that through electronic media (e.g. Zoom and Teams) we can all operate almost just as efficiently as before. I believe this offers new opportunities for our world congresses, in that many of the very top political and agency leaders (e.g. the World Bank) might not have had the time to travel long distances to address our congresses as a keynote speaker in the past. However, through current electronic media and the experience and confidence we have all gained in using such technology through this pandemic, we can now invite some of the world’s leading figures, with an interest in and responsibility for the water sector to address our congresses from their office, thereby avoiding extensive travel time etc. In my view this lesson learnt gives us an opportunity to be really imaginary in terms of the speakers we can invite to open our congresses in the future.

The COVID-19 health crises has been terrible for so many citizens worldwide and it is perhaps premature to discuss the lessons learnt from this crises. However, IAHR is a global organisation with members across the world and all working at different time zones. One thing that COVID-19 has taught us is that through electronic media (e.g. Zoom and Teams) we can all operate almost just as efficiently as before. I believe this offers new opportunities for our world congresses, in that many of the very top political and agency leaders (e.g. the World Bank) might not have had the time to travel long distances to address our congresses as a keynote speaker in the past. However, through current electronic media and the experience and confidence we have all gained in using such technology through this pandemic, we can now invite some of the world’s leading figures, with an interest in and responsibility for the water sector to address our congresses from their office, thereby avoiding extensive travel time etc. In my view this lesson learnt gives us an opportunity to be really imaginary in terms of the speakers we can invite to open our congresses in the future.

Picture: Pollutants from Agriculture Discharged into a Stream, Transported via Hydrodynamic and Sediment Transport Processes to the River Basin and then the Coast.

COVID-19 has affected the world in many ways. What challenges in terms of water security has it brought? Is this a strong impediment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda?

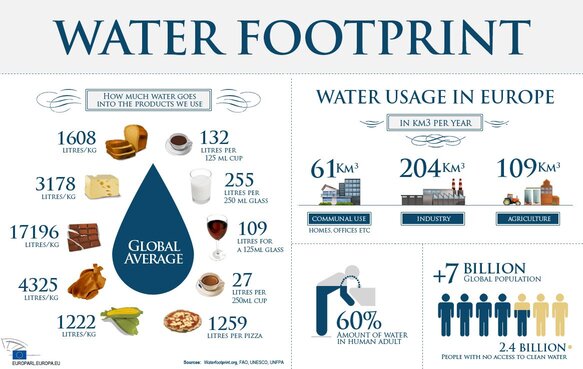

COVID-19 has created many challenges in terms of water security and, most notably, what are the effects of the disease in entering the water system and how does the disease advect and diffuse through the system? However, it has also brought many opportunities in terms of global water security. For example, it has made the world’s population think more about protecting nature (including water); it has made us appreciate more our aquatic and marine ecosystems services and biodiversity; it has made us think more about virtual water and the impact of developed nations on the security of good quality water in less developed nations (for example, do we need to buy so many clothes, where the cotton is produced in less developed nations, and using and polluting their water to produce these clothes); it has made us think more about the UN SDGs and, for example, do we need to fly so frequently, thereby: increasing Greenhouse Gas Emissions, increasing global temperatures, increasing the severity of floods and droughts? These are just some of the challenges and opportunities where IAHR can contribute to the delivery of the UN SDGs.

The Water Footprint (or virtual water) is illustrated above for many basic commodities where one country can have a significant impact on the water security of another country: IAHR has much to contribute in providing the expertise to ensure that, for example, the virtual water used in coffee production is returned to the ecosystem of high quality.

Recently you were a speaker in the IAHR webinar on “The Business of Global Water Security: Linking Knowledge to Practice”, could you briefly summarize and reflect on the main outcomes of the webinar?

The IAHR webinar was extremely successful and evidenced by the fact that we had over 4,700 page views on the day and many downloads of the presentations since. The main points to have come out of the webinar were that global water security (i.e. security in terms of good quality water and as much as needed) is an increasingly important topic of global interest and with water now being centre stage with world political and business leaders. The impacts of climate change on the water cycle are having dramatic effects by increasing floods and droughts, and rapidly growing economies are increasing the global water stress through water trading via virtual water etc. As demand for better quality water and the sustainable protection of aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity increases, then the business opportunities for better water management are also increasing worldwide. 70% of the world’s freshwater is currently used in agriculture. The investment that has gone into irrigation and water supply and water quality management is small compared to the research and development advances in other industries, e.g. the automotive industry. This is exemplified by the current methods of irrigation which, in general, have not advanced much over the past half century. New technology in remote sensing, real-time data acquisition, artificial intelligence and experimental and modelling techniques, as well as new methods of farming (e.g. vertical farming) all offer considerable opportunities to improve our management of the water cycle and produce ‘more crop per drop’. IAHR offers an excellent platform to deliver many of these technologies and to contribute significantly to addressing the UN SDGs.

Could you please provide some advice to young IAHR professionals working (or willing to work) in the “Business of Global Water Security”?

I would just like to make the following points to my ‘young IAHR professional’ colleagues: (i) ‘The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 3.575 million people (mainly children) die from water-related diseases a year’ (WHO 2019); (ii) ‘2.3 billion people affected by flooding disasters in 20 years’ (Aug. 2017, Channel 4 News); (iii) ‘More than 50 million people face hunger crisis due to African drought’ (Nov. 2019, The Weather Channel); etc. These are just three examples from the media that highlight some of the many business challenges and opportunities we face in terms of addressing global water security. IAHR contributes considerably and continuously into acquiring and promoting a better understanding of all aspects of the water cycle and, through the research and engineering developments of IAHR’s members, IAHR continues to provide a truly international platform for us to improve water security at a global scale.

Hydro-epidemiological predictions of e.coli levels from the Ribble Basin to the Fylde Coast (UK), with (left) and without (right) sediment coupling, highlighting the importance of sediment transport as a means of transporting e.coli from catchment to coast

Our members, their views, knowledge, commitment, and experiences are what make IAHR a global leading association of hydro-environmental engineers, experts, researchers, and organisations. IAHR members’ voices and concerns guide the association on its continuing path towards a better future for water and the environment. Our members have a lot to contribute and we are listening to them so that we can put our collective voice forward.