Pakistan Floods 2022 – An Interview by the IAHR President to Share Expert Insights

Pakistan is the latest example of how tragic the consequences of increasing weather extremes associated with climate change can be. It is particularly ironic at a time that several parts of the world (most notably China, Africa, Europe and the western United States) have experienced historic droughts in the past few months (Copernicus, 2022). Pakistan is particularly vulnerable to extreme floods as the headwaters of much of the country lie in mountainous areas with large volumes of snow and the headwaters contain the largest volume of glacial and mountain ice outside the polar regions. The combination of an abnormal March heatwave followed by an unusually intense monsoon resulted in unprecedented runoff.

Since June 2022, devastating floods have inundated a large part of Pakistan and caused enormous damages. Water area in the three most severely hit provinces – Sindh in the south, Baluchistan in the south-west, and Punjab in the east – have increased from 18,113 km2 to 33,532 km2, since the flood happened. By August 30, 29%, 4% and 30% of farmland in these three provinces have been flooded. Flooding covers an area the size of the United Kingdom and has wiped out major roads, cutting off the transport links with the northern provinces. By September 11, fatality count from the floods has reached 1,400, with another 12,588 injuries, over 1 million houses damages, 500 bridges destroyed, and a population of 33 million affected. This flood has put the provisional cost of the catastrophe at more than US$30 billion, according to the Pakistan government's flood relief center.

To facilitate the global water research and engineering community in understanding what is happening in Pakistan, President of IAHR Prof. Joseph Hun-wei Lee invited four IAHR experts to share their unique insights in an interview conducted in September 2022. The following is a summary of the recent Pakistan flood - in the spirit of informing public policy and in the hope of inspiring future actions.

An aerial view of a flooded residential area in Sindh Province, southeastern Pakistan (Source: UNICEF/UN0696544/Zaidi)

An aerial view of a flooded residential area in Sindh Province, southeastern Pakistan (Source: UNICEF/UN0696544/Zaidi)

1. Abnormal monsoon and heavy rainfalls

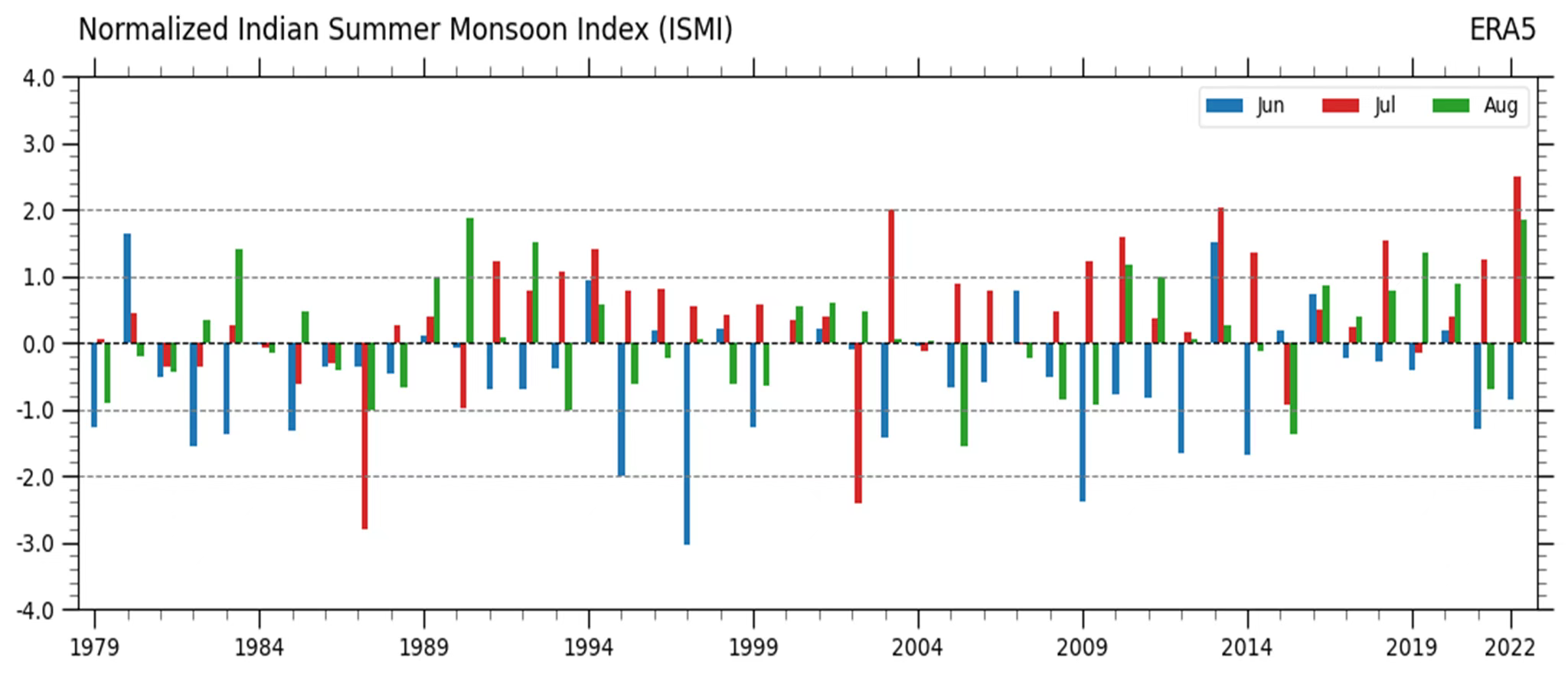

The Indian summer monsoon index in July 2022 reached 2.5, which is the highest record in history. It is the record high monsoon index that has brought Pakistan heavy rainfalls, causing destructive flash floods in the mountainous north, and the widespread flooding in the southern plains. It has received five times more rain than normal in 2022. Multiple surface rainfalls exceeding 300 mm are devastating for places that have an average annual precipitation of about 100 mm. Padidan, a small town in Sindh province, has been drenched by more than 1,800 mm since the monsoon began in June, according to an AFP news item.

Prof. Cui Peng, an Academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Director of the China-Pakistan Joint Research Center on Earth Sciences (CPJRC), noted the Indian Summer Monsoon Index in July and August 2022 was the strongest of the historical record. The intensity was more than twice stronger than usual and continued to be extremely strong in July and August. The correlation between Indian Summer Monsoon Index and the precipitation anomaly is positive in southern Pakistan in July.

Monthly Indian Summer Monsoon Index for June, July and August from 1979 to 2022 (Source: LIN Zhaohui, Victor Dike, ZHANG Huiwei, WANG Yan, China-Pakistan Joint Research Center on Earth Sciences)

Monthly Indian Summer Monsoon Index for June, July and August from 1979 to 2022 (Source: LIN Zhaohui, Victor Dike, ZHANG Huiwei, WANG Yan, China-Pakistan Joint Research Center on Earth Sciences)

2. Comparison with the floods in 2010

In 2010, over 20 million people were affected by floods in Pakistan due to the jet stream and summer monsoon. The flood of 2022 is even worse than 2010, with 33 million people affected so far. The flood of 2010 was mainly from the upper Indus River, where overtopping floods caused the downstream embankments to collapse, creating several large breaches and large inland lakes in low-lying areas outside the river. While the flood of 2022 was mainly caused by the local heavy rainfall. Although the causes of these two floods were different, the extent of the inland lake was basically the same.

Prof. Cheng Xiaotao, former vice chair of IAHR’s Technical Committee on Flood Risk Management who visited Pakistan to provide technical aids in 2010 after the historical flood, noted the inland lake formed now and the scope of the inland lake in 2010 basically overlaps, because the current flooding area is actually the ancient river channel of the Indus River. The inland lake was formed here after the flooding from the broken dike entered the ancient river channel area. This area is the best irrigated agricultural area in Pakistan. Both flood disasters were heavy because the main population was distributed near this irrigation area. The flood water in the inland lake cannot be discharged and has to be dissipated by evaporation and infiltration. As a result, the irrigation area is likely to be under water for a long time, and the houses and food on which the residents depend cannot be used, and transportation is interrupted, making recovery and reconstruction extremely difficult.

Large areas in Sindh, Pakistan remained flooded in October 2010 (Source: Prof. Cheng Xiaotao)

Large areas in Sindh, Pakistan remained flooded in October 2010 (Source: Prof. Cheng Xiaotao)

3. The suspended and wandering Indus River

Soil erosion is severe in the Indus basin, where the middle and lower reach is a wandering channel, the siltation of which leads to the formation of a suspended river. Flood from the suspended river spills outward to be stored for a long time in the low-lying areas outside the river channel, with nowhere to drain and difficult to return to the river channel, thus forming an enormous inland lake located at the border of Sindh and Baluchistan that covers an area of more than 4,727 km2, with a maximum length of 330 km and a maximum width of 21 km. The area covered by the inland lake is also the most affected area of this flood. Over ten thousand buildings and 1,246 km of roads have been underwater in this inland lake.

Prof. Cao Wenhong, a sediment expert and former chief engineer of the China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research (IWHR), noted the morphology of lower Indus River is close to that of the Yellow River, which is also a wandering river with serious sediment deposition. The lower reaches of the Indus River are broad and gentle, with low sediment transport capacity, and strong lateral swing. In addition, the embankment is weak, easy to cause the river horizontal expansion and roaming, which is very unfavorable to the safety of the surrounding area.

Map of Pakistan (Source: WorldAtlas.com)

Map of Pakistan (Source: WorldAtlas.com)

4. Is it glacier lake outburst flood?

Discussions about the contributions of glaciers to the floods this year were reported by NPR, CNN, etc. However, our experts believed that, based on the information available so far, it is inferred that there is not very strong or convincing relationship between this flood and the GLOF (glacier lake outburst flood).

GLOF usually occurs in May and June, while this flood started in July and August. Glacier lake outbursts are generally localized disasters that are difficult to spread from mountains to plain areas thousands of kilometers downstream. Many reservoirs were built upstream of the Indus River. These reservoirs were not put into emergency release until August, indicating that they have acted as a barrier to upstream flooding.

Also, after the flood formed by the melting glaciers reach the plains, it has a sawtooth flow characteristic, with a consequent increase in flow during the day due to high temperatures and a decrease in flow at night when temperatures drop, which is different from the peak shape caused by heavy rainfall.

5. Attribution to Climate Change

UN Secretary-General António Guterres speaking with the BBC on September 15 emphasized that assisting Pakistan is a matter of justice not just humanitarian aid and was quoted saying:

"Pakistan is not responsible for this crisis, this was a product of climate change, this was caused by those that are populating the atmosphere with greenhouse gases. The G20, the biggest economies in the world, represent 80% of the emissions, Pakistan less than 1%."

Prof. Peter Goodwin, Past President of IAHR who also serves on the Maryland Commission for Climate Change, noted the degree to which climate change worsened the unfolding tragedy in Pakistan will be the subject of numerous scientific analyses in the coming months. Preliminary estimates by World Weather Attribution (link 1 and link 2) indicate that the event was approximately the 1 in 100-year event. For Sindh Province the 5-day maximum rainfall was about 75% more intense than would have occurred without global warming and the 60-day regional rainfall was about 50% more intense. However, the researchers take care to detail the uncertainties in the analyses due to the extreme variability of precipitation in the region and the difficulty of current precipitation models to predict the intensity of the observed episodic rainfall events.

Unfortunately, the flood disaster does not end as the floodwaters recede in the coming weeks. Infrastructure must be rebuilt, agriculture must recover and massive humanitarian aid will be required to avert food shortages. Increasing incidence of disease compounded by damage to the infrastructure of healthcare systems will result in further devastation to communities. Dengue fever and malaria are just some of the rising healthcare crises facing the regional health authorities as many roads continue to be impassable. Although the complete human toll resulting from these floods will not be known for many months, it is a poignant reminder of the secondary effects of climate change and that the most vulnerable countries have often contributed the least to carbon emissions and the climate crisis.

Displaced families making their own shelters in Sindh without clean water (Source: BBC)

Displaced families making their own shelters in Sindh without clean water (Source: BBC)

6. Looking ahead: international cooperation

The factors and mechanisms of the current inland lake formation are complicated. Further in-depth investigation and research would be required before developing targeted prevention and control programs. The irrigation areas on both sides of the downstream Indus River are well developed, and agriculture mainly depends on irrigation. This flood has produced devastating damage to the entire irrigation system, and recovery will not be achieved easily.

The numerous victims and damaged houses resulting from the massive flooding, and the large inland lake are problems that cannot be resolved in a short time for Pakistan, which is still economically underdeveloped. It will take a lot of time and assistance from the international community to gradually help restore the situation to what it was before the disaster.

How to improve the existing embankment system, how to deal with the agricultural areas and population in the ancient rivers, and how to manage and control the wandering rivers are all difficult issues that will take a longer time to study.

The China-Pakistan Joint Research Center on Earth Sciences provides a platform for international cooperation. Established jointly by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Higher Education Commission of Pakistan in 2019 with the mission of studying and evaluating the impact of geo-hazards and climate change and also the sustainable development of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the center welcomes international cooperation and is sharing datasets such as the flood distribution in Pakistan on its website.

Authors

Cui Peng

Joseph Hun-Wei Lee

President, IAHR

Fellow, Royal Academy of Engineering

President, Macau University of Science and TechnologyCui Peng

Academician, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Director, China-Pakistan Joint Research Center on Earth SciencesCheng Xiaotao

Past Vice Chair, Technical Committee on Flood Risk Management, IAHR

Former Deputy Chief Engineer, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research

Member of the expert team, China National Disaster Reduction CommitteeCao Wenhong

Former Chief Engineer, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research

Director, Research Center on Soil & Water Conservation, Ministry of Water Resources of ChinaPeter Goodwin

Past President, IAHR

President, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science

Vice-Chancellor for Environmental Sustainability, University System of Maryland

Member, Maryland Commission for Climate Change